Great news this month – we’ve just announced a fantastic new sponsor. For the first time in the company’s history, Rolls-Royce is sponsoring a World Land Speed Record project. Its engines have been used since the early days of record breaking, and they created what was probably the most successful record power-plant ever: the 37-litre, V-12 ‘Type R’, which became the only engine in history to set Air, Water and Land Speed Records in the 1930s.

1935 – 300 mph of Rolls-Royce power

1935 – 300 mph of Rolls-Royce power

Rolls-Royce is also heavily involved in the Bloodhound Education Programme, with some 50 company employees having volunteered to become Bloodhound Ambassadors. We have around 5500 schools registered with our Education Programme, so the only way we can get to them all is with the support of hundreds of volunteers. If you fancy inspiring groups of schoolchildren and getting involved with our ‘Engineering Adventure’, then please get in touch with our Ambassador Programme.

Rolls-Royce has also been giving us a huge amount of technical support. Our EJ200 jet engine, manufactured by Rolls-Royce and its EuroJet partners, was designed solely to power the Typhoon aircraft: we are the first people ever to put it in another vehicle, and it’s a complex process. Rolls-Royce has been advising us on engine cooling, intake design, fuel systems – you name it. The engine is fully fly-by-wire, so they have also been helping us to develop Bloodhound’s control systems, which will link my throttle pedal to the engine.

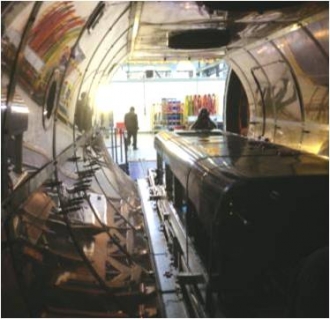

Early on in the life of the Project we were loaned three EJ200 development engines that had come to the end of their flight-test lives and were destined for museums. However, the engines have just enough hours left (aircraft component life is measured in hours) for us to run up and down a desert racetrack.

Typhoon in a box

Typhoon in a box

Last month we tested one of these engines with our own electronics, using the same circuits that will go into Bloodhound SSC. This is the first time that anyone had ever tried to do this, so it was a big moment for our engineers. The EJ200 has 2 digital engine control channels – effectively it has 2 ‘brains’, so that if one has a problem then the other can take over immediately. The engine needs a huge range of information from the Eurofighter Typhoon aircraft, including air speed, temperature and pressure, as well as the pilot’s control inputs. While you’re reading this, the next time you decide to move the computer mouse, it will take about 220 milliseconds for the nerve signals to reach your hand. In that time, the EJ200 will receive 20 messages, each containing over 30 pieces of information for the engine.

To achieve this, Rolls-Royce has a huge computer room to simulate the Typhoon aircraft’s control inputs. By contrast, Bloodhound systems engineer Joe Holdsworth achieved much of the same effect with something the size of a sandwich box – and it worked perfectly. This is a huge achievement by Joe, but I was a little disappointed, as was the BBC. We were due to go and see Joe’s engine runs, but they were so successful that he had finished before we get there. At this rate, I’ll never get to see the engine run – next time we test it, I’ll be in the Car!

Lower chassis – done to perfection

Lower chassis – done to perfection

The chassis build is also coming along well. The rear lower chassis is now finished, with huge thanks to the National Composites Centre for ‘cooking’ it perfectly to cure the bonding agent. We were a little concerned over distortion due to the unequal expansion of the steel, aluminium and titanium, but the end result was almost perfect – less than 2 mm of distortion over the 4 m length.

The finished chassis member is now being mounted on the 7 metre ‘surface table’ (a very large flat piece of steel), using ‘cups and cones’, which are simple cup-shaped and cone-shaped fittings (the clue’s in the name) bolted to the chassis and the table, and which locate the chassis back in exactly the same place each time we move it.

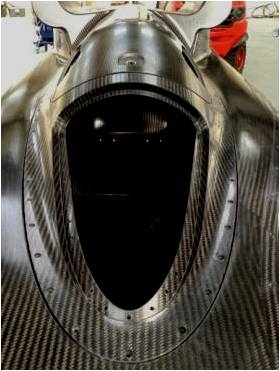

1000 mph Office – in need of interior decoration

1000 mph Office – in need of interior decoration

We’ve now got the rest of the cockpit carbon fibre pieces, which all fit perfectly, thanks to the great work by URT. For the first time I can see the 1000 mph office looking complete – and it’s very dark in there. We’ll be painting it some nice light airy colours before it’s finished, to make it look a bit less dark and scary, and so that I can see what I’m doing.

We’ve also received our first suspension pull rod, which is now off to AMRC for testing. Each wheel moves up and down on double wishbones, with a diagonal ‘pull rod’ taking the loads. For Bloodhound SSC, the loads are quite high.

15 tonne pull rod

15 tonne pull rod

Last week, I had dinner with some of the Ferrari F1 team in Oxford, after a lecture by team principal Stefano Domenicali (in which he tried to recruit some more engineers – it’s not just this country that’s short of them). We compared pull rods – the Ferrari suspension is stressed to take about 10 kN (one tonne). For Bloodhound, the pull rod is designed to take 154 kN – that’s a little over 15 tonnes (to cater for the extreme case of a 5G bump). Put another way, you could pick up a Ferrari F1 car just by using of its pull rods. You could pick up every F1 car on the grid at the same time using one of Bloodhound SSC’s....

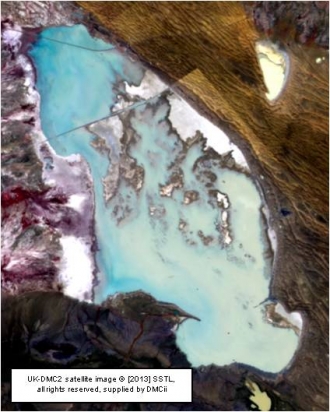

After the recent flooding of our Hakskeen Pan track in South Africa, we’ve been watching carefully to see how the surface dries. We’re getting invaluable information from regular satellite photos of the Pan, using pictures from the Disaster Monitoring Constellation, a British-operated network of earth-observation satellites (a British engineering success in its own right).

Look closely – Rudi’s down there somewhere....

Look closely – Rudi’s down there somewhere....

The satellite image shows water up as light blue, with deeper water shown as darker colours. This picture shows very shallow coverage over most of the Pan. The tarmac road can be seen on the northern end andof the pan, and the old causeway shows up clearly about one-third of the way from the top. The centre section of the causeway has been removed and the surface precision-graded by the Northern Cape team, so this is the bit that we are really interested in.

The very shallow water along the old causeway indicates a very slight depression (perhaps one centimetre deep), which is fine – that’s much better than hitting a bump at supersonic speeds! We were lucky that our Track boss, Rudi Riek, was on the Pan on the same day. His survey of the flooded areas ties up exactly with the satellite picture, confirming for us that this is an accurate method of tracking flood water and surface drying.

In a few weeks’ time, once the surface is completely dry, we’ll be doing a laser scan survey of the whole track. This will give us precise data on the surface and the causeway area. By the time we start to run the Car next year, we’ll know exactly what to expect.