On the 20th of June 2011, the green flag was finally given signaling the return of 300 workers to Hakskeenpan after almost seven months of heavy rain and flooding.

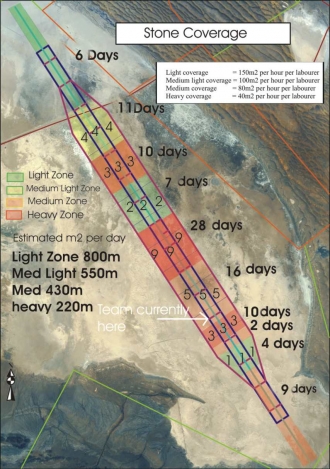

The crew of 300 people split into 15 teams have, including last year’s 9 days, worked a total of 29 days at the time of writing this article. They have cleared 500m x 14km of track thus far and have another estimated 90 days of work ahead of them.

All indications are that our estimates with regards to the rate of progress where spot on as seen in the diagram on the right.

All indications are that our estimates with regards to the rate of progress where spot on as seen in the diagram on the right.

Although the picture on the right is very positive the team is effectively done with only a third of the stone removal and tough times still lay ahead as we are now beginning to enter spring and much hotter conditions. The mental high the team will reach in about two weeks time when they have completed the central track will be immediately replaced the following day by the knowledge that they have to do it all over again - twice! As the safety zones still lie ahead. It is grueling work and only the toughest have remained onboard as many team members have already been replaced.

The unusually high rainfall had one very positive effect, the area that was cleared before the rain, approx 500m x 6km is as close to perfect as it could ever be, all signs of disturbance have been erased and it solidly cemented the theory we all had until now that the rain would be our ally. We initially had fears that new rocks would emerge or that the rocks would migrate with the water but fortunately this was not the case.

The team is currently awaiting the return of the earth moving equipment to continue with the elevated road’s removal in addition to the stone removal.

The team is currently awaiting the return of the earth moving equipment to continue with the elevated road’s removal in addition to the stone removal.

The area the team is currently in still has quite heavy stone coverage and the rate of progress is about 500m x 500m per day. It is back breaking work as not only are there tonnes of stones, but all of them, even the smallest one are lodged into the clay. Generally the process is that each of the 15 teams is made up of 20 workers with a team leader, each team has 12 spades, 2 wheelbarrows, 5 buckets and four brooms. The spade men dislodge the stones and scrape them into small piles, the bucket people pick up the piles and throw them into the wheelbarrows, the wheelbarrow guys walk - if you are unlucky and in the middle of the track, 500m round trip to deposit the stones and the broom people do the final sweep up. No vehicles have been allowed on the central track.

In the pictures above it is clear just how many stones are being removed, remember you are only seeing one side of the track, the picture is the same on both sides, we estimate it to be about one ton of stones every 10m for at least 5km of the track as they have just completed the one heavy coverage areas. Calculators out... 1000kg x 100 (every 10m) x 5km x 2(sides) = 1000 000 kg of rocks all removed one by one by hand :) (Welcome to the Kalahari.. Have a nice day) the process of removing these piles of rocks will start shortly.

In the pictures above it is clear just how many stones are being removed, remember you are only seeing one side of the track, the picture is the same on both sides, we estimate it to be about one ton of stones every 10m for at least 5km of the track as they have just completed the one heavy coverage areas. Calculators out... 1000kg x 100 (every 10m) x 5km x 2(sides) = 1000 000 kg of rocks all removed one by one by hand :) (Welcome to the Kalahari.. Have a nice day) the process of removing these piles of rocks will start shortly.

The picture above on the left was taken in July last year (2010) when we did the first test stone removal, the picture on the right is of the exact same position taken this week, a year later. Notice the disturbed clay on the left where rocks had been removed, a year later they are all completely smoothed out and level. This is very exciting news as it proves that we do not have to be concerned about minor disturbances created as nature will sort them out for us.

Penetrometer readings

Seen in the light of the above observation, the picture left which is of an area cleared this week is of no concern to us as it has been proven that with sufficient water the small holes you see will be smoothed out naturally in time.

Seen in the light of the above observation, the picture left which is of an area cleared this week is of no concern to us as it has been proven that with sufficient water the small holes you see will be smoothed out naturally in time.

As Andy explained in his article on the cone penetrometer, it is a hand held probe, designed by the military for simple and rapid measurement of surface hardness.

While there is no exact limit for minimum hardness, we are looking for a Cone Index of over 150, and preferably over 200, to run the car.

We have done previous readings of the pan and always found readings between 200 and greater than 290. With between 300mm and 500mm of rain recorded in the area recently we expected the entire pan to be much softer as it only dried up about a month ago. Surprisingly we measured readings of greater than 290 for the entire track and safety zone other than one soft area, the northern safety zone. The reading at the fence adjacent to the tar road in the North was only 130 and it gradually climbed to 290 approx 500m before the start of the actual track. We speculate the reason for this is that the elevated tar road produced its own microclimate as all the runoff from the road added to the volume of water in this area. I think we will have bigger problems than a slightly soft surface if the vehicle ever ends up at the fence however.

In conclusion, there is still a long road (track) ahead but after spending time with the team on the pan I feel nothing but pride and admiration for what the Northern Cape government has achieved thus far. Three hundred families from five towns now have an income for the first time in a very long time and the work they have done until now is epic in scale. We are well on our way to creating the world’s fastest race track.

In conclusion, there is still a long road (track) ahead but after spending time with the team on the pan I feel nothing but pride and admiration for what the Northern Cape government has achieved thus far. Three hundred families from five towns now have an income for the first time in a very long time and the work they have done until now is epic in scale. We are well on our way to creating the world’s fastest race track.

Rudi Riek

Track Boss