A History of the world land speed record

The Land Speed Record is motorsport distilled to its most fundamental elements: Distance versus time.

Seeking records is no sinecure. There is none of the adrenaline rush of mano a mano wheel-to-wheel competition of Grand Prix racing. None of the glamour and glitz that surrounds Lewis Hamilton and Felipe Massa, McLaren and Ferrari.

Teams all too frequently find themselves far from civilisation, in some of the least hospitable yet breathtakingly beautiful parts of the globe. They are at the mercy of Mother Nature, praying it won’t rain while eyeing the curvature of the earth and fighting the potentially fatal ennui of isolation in the times when their car is not ready to run. This is a particularly cold-blooded pursuit that demands a very special brand of courage and determination.

And it is a peculiar measure of a man, an unusual means of judging his claim to heroic status, though self-aggrandisement is rarely part of his personal credo. There have been few speed kings who have not been reluctant heroes.

In the beginning, the battle was between different types of propulsion. First electricity and then steam fought it out, then came the internal combustion automobile engine. That fell victim to its much more powerful aeronautical counterpart, before that, too, was dismissed to the pages of history by turbojet and rocket engines.

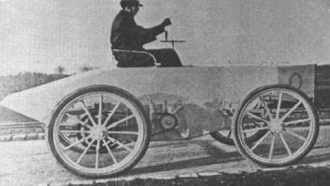

At the turn of the 20th century Count Chasseloup-Laubat and the red-bearded Camile Jenatzy fought a duel in their respective electric cars, a Jeantaud and ‘Le Jamais Contente’ that saw the record rise from the former’s 39.24 mph in December 1898 to the latter’s 65.79 mph four months later. Then came Leon Serpollet’s 75.06 mph in a steam-powered car of his own design in April 1902.

At the turn of the 20th century Count Chasseloup-Laubat and the red-bearded Camile Jenatzy fought a duel in their respective electric cars, a Jeantaud and ‘Le Jamais Contente’ that saw the record rise from the former’s 39.24 mph in December 1898 to the latter’s 65.79 mph four months later. Then came Leon Serpollet’s 75.06 mph in a steam-powered car of his own design in April 1902.

Thereafter, contenders used Mors, Gobron-Brillie, Mercedes, Darracq, Napier, Benz and Sunbeam racing cars to kick the mark to 133.75 (courtesy of Kenelm Lee Guinness in an aero-engined Sunbeam) by May 1922.

Great eras followed. In the Twenties race drivers Henry Segrave, Malcolm Campbell, Parry Thomas and Kaye Don fought for British honour with American rivals Ray Keech and Frank Lockhart, edging the record to Segrave’s 231.44 mph with Golden Arrow in March 1929.

The early Thirties belonged to Campbell. Thomas was dead, killed at Pendine Sands in 1927; Segrave had died on Windermere in June 1930. Steadfastly, Campbell pushed his own mark ever upward with his famous Bluebird, leaving it at 301.129 mph in September 1935. Thereafter fellow race drivers George Eyston and John Cobb, with Thunderbolt and Railton Special respectively, set three records apiece. On Cobb’s last, 394.20 mph in September 1947, one run yielded an average speed of 403 mph, the first time 400 mph had been attained on land.

The early Thirties belonged to Campbell. Thomas was dead, killed at Pendine Sands in 1927; Segrave had died on Windermere in June 1930. Steadfastly, Campbell pushed his own mark ever upward with his famous Bluebird, leaving it at 301.129 mph in September 1935. Thereafter fellow race drivers George Eyston and John Cobb, with Thunderbolt and Railton Special respectively, set three records apiece. On Cobb’s last, 394.20 mph in September 1947, one run yielded an average speed of 403 mph, the first time 400 mph had been attained on land.

The greatest gathering of contenders, at the Bonneville Salt Flats in 1960, saw American Athol Graham killed; Art Arfons and Dr Nathan Ostich fail; ingenious Mickey Thompson denied success by a footling driveshaft failure; and Campbell’s son Donald, the sole defender of British pride, crash his turbine-engined Bluebird at 325 mph.

Campbell returned to set a new wheeldriven record of 403.1 mph in July 1964. But soon the turbojet ruled the roost as Arfons and Californian rival Craig Breedlove played a high-speed game of Russian roulette on the flats which pushed the record to 600.601 mph by November 1965 and saw both contenders lucky to survive serious accidents which destroyed their respective machines, Green Monster and Spirit of America.

In October 1970, Gary Gabelich’s Blue Flame ushered in the rocket era with 622.407 mph.

In October 1970, Gary Gabelich’s Blue Flame ushered in the rocket era with 622.407 mph.

Records must officially be ratified by the FIA, the governing body of motorsport, and are the average of the elapsed time for two runs, made within an hour and in opposing directions over a measured mile or kilometre. Where a contender breaks both the mile and kilo records, the practise is to recognise the former since it is the greater distance. Thus Gabelich’s 622.407 mph was the land speed record even though Blue Flame averaged 630.388 mph through the kilometre.

Thirteen years later, Richard Noble’s Thrust2 regained the record for Britain at 633.468 mph on October 1983, and there things settled until his ThrustSSC, driven by Andy Green, reached 714.144 mph in September 1997.

That was just a prelude, however, for on October 15 Green became the first man ever to exceed the speed of sound at ground level, at 763.035 mph. He remains the only supersonic speed king in history.

Some speak in awed tones of witnessing an eclipse of the sun, of seeing the Northern Lights or a shooting star. But to stand on a playa desert, watching what in turns seems to be a mirage, a boat, a big black locomotive and then, for fleeting moments, ThrustSSC, chased by its own roostertail of dust, and then to hear the two unmistakeable sonic booms, is to experience a moment so emotionally charged that all others pale in comparison.

There is a sensual beauty and an intense nobility to it all that has entranced a special breed of man for more than a century.